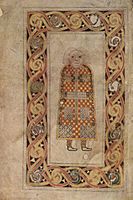

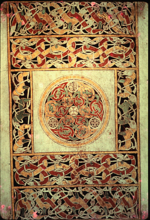

The Man of Matthew Book of Durrow Northeast England C 650 Insular Art

The Book of Durrow is an illuminated manuscript dated to c. 700 that consists of text from the four Gospels gospel books, written in an Irish adaption of Vulgate Latin, and illustrated in the Insular script style.[1]

Its origin and dating has been field of study to much debate. The book was created in or almost Durrow, County Offaly, on a site founded by Colum Cille (or Columba) (c. 521-97), rather than the sometimes proposed origin of Northumbria, a region that had close political and creative ties with Ireland, and like Scotland, likewise venerated Colum Cille.[2] [3]

Historical records bespeak that the volume was probably at Durrow Abbey by 916, making it one of the earliest extant Insular manuscripts.[1] It is desperately damaged, and has been repaired and rebound many times over the centuries.[ane] Today information technology is in the Library of Trinity College Dublin (TCD MS 57).[four]

Clarification [edit]

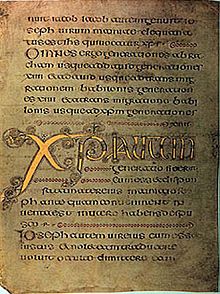

The starting time of the Gospel of Mark from the Book of Durrow

It is the oldest extant complete illuminated Insular gospel volume, for case predating the Book of Kells by over a century. The text includes the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, plus several pieces of prefatory matter and canon tables. Its pages measure 245 by 145 mm and at that place are 248 vellum folios. It contains a large illumination programme including six extant rug pages,[two] a full page miniature of the four evangelists' symbols, iv full folio miniatures, each containing a unmarried evangelist symbol, and vi pages with pregnant decorated initials and text. It is written in upper-case letter insular script (in effect the block capitals of the day), with some lacunae.

The folio size has been reduced by subsequent rebindings, and almost leaves are at present single when unbound, where many or virtually would originally have been in "bifolia" or folded pairs. It is clear that some pages have been inserted in the wrong places.[two] The master significance of this is that information technology is unclear if there was originally a seventh carpet folio. Now Matthew does not have one, merely there is, most unusually, ane every bit the concluding page in the volume. Mayhap there were simply ever six: one at the showtime of the book with a cross, 1 contrary the side by side folio with the four symbols (as now), and 1 contrary each individual symbol at the first of each gospel.[5] Otherwise the original programme of illumination seems to be complete, which is rare in manuscripts of this age.

In the standard business relationship of the development of the Insular gospel volume, the Book of Durrow follows the bitty Northumbrian Gospel Book Fragment (Durham Cathedral Library, A. Ii. 10.) and precedes the Book of Lindisfarne, which was begun around 700.[six]

Illumination [edit]

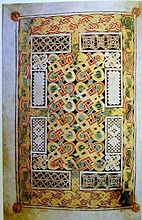

Carpeting page with interlaced animals

The illumination of the volume shows specially well the varied origins of the Insular style, and has been a focus for the intense art-historical discussion of the event. Ane thing that is articulate is that the artist was unused to representing the human figure; his primary attempt, the Homo symbol for Matthew, has been described equally a "walking buckle".[7] Apart from Anglo-Saxon metalwork, and Coptic and Syriac manuscript illustrations, the effigy has been compared to a bronze effigy with a console of geometric enamel on his body, from a bucket found in Norway.[viii]

The animal iconography derives from Germanic zoomorphic designs; the depictions of the Jesus and the Evangelists from Pictish stones. The geometric borders and the carpeting pages cause more disagreement. The interlace, like that of the Durham fragment, is mostly large compared to the Book of Lindisfarne, just the farthermost level of detail found in later Insular books begins here in the Celtic spirals and other curvilinear decoration used in initials and in sections of carpeting pages. The page illustrated at left has animal interlace effectually the sides that is fatigued from Germanic Migration Catamenia Fauna Style II, as found for example in the Anglo-Saxon jewellery at Sutton Hoo, and on the Benty Grange hanging bowl. Just the circular panel in the centre seems, although not as precisely every bit other parts of the book, to describe on Celtic sources, although the 3 white circles at the edge call back Germanic metalwork studs in enamel or other techniques.

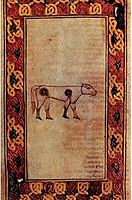

The Book of Durrow is unusual in that it does not use the traditional scheme, usual since Saint Jerome, for assigning the symbols to the Evangelists. Each Gospel begins with an Evangelist'south symbol – a human being for Matthew, an eagle for Mark (not the lion traditionally used), a calf for Luke and a lion for John (not the eagle traditionally used). This is too known equally the pre-Vulgate system. Each evangelist symbol, except the Man of Matthew is followed past a carpet folio, followed by the initial page. This missing carpet page is causeless to accept existed. A first possibility is that it was lost, and a 2d that it is in fact folio 3, which features swirling abstract decoration. Where the four symbols announced together on page 2r they appear in the normal gild if read clockwise, and in the pre-Vulgate order if read anti-clockwise, which may exist deliberate.[nine]

The first alphabetic character of the text is enlarged and busy, with the following letters surrounded past dots. Parallels with metalwork can be noted in the rectangular body of St Matthew, which looks similar a millefiori ornamentation, and in details of the carpeting pages.

There is a sense of space in the design of all the pages of the Book of Durrow. Open vellum balances intensely decorated areas. Fauna interlace of very loftier quality appears on folio 192v. Other motifs include spirals, triskeles, ribbon plaits and circular knots in the carpeting pages and borders around the Four Evangelists.

Evangelists' symbols [edit]

-

The Man of Matthew (folio 21v)

-

The Ox of Luke (folio 124v)

-

The Lion, hither of Mark (folio 191v)

History [edit]

Origin [edit]

The book is named later on a monastery in Durrow, County Offaly, founded past Colum Cille late in his life, while he was abbot of Iona. Although Colum Cille founded monasterys in Ireland, Scotland and the early medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom Northumbria in today's Northern England, a consensus amongst scholars is that the book was produced at Durrow, c. 700.[2]

The colophon of the book (f. 247r) contains an erased and overwritten note which, according to one estimation, is by "Colum" who scribed the volume, which he said he did in twelve days. This probably relates to the belief that Colum Cille (Saint Columba) had created the volume, but its date and authenticity is unclear. Twelve days is a plausible time to scribe 1 gospel, but not four, however less with all the decoration.[10] What is known for certain is that Flann Sinna (877-916), High King of Ireland, deputed a silver plated cumdach, or metalwork reliquary for the book.[11] [2] The shrine is the primeval known cumdach, but is long since lost. It was once believed to contain a relic of Colum Cille.[12]

Preservation [edit]

A blank page contains a note by the Durrow scribe Flannchad Ua hEolais, probably from around 1100, relating to a legal dispute.[11] The shrine was lost in the 17th century, but its appearance, including an inscription recording the king'southward patronage, is recorded in a note from 1677, now bound into the book as folio IIv, although other inscriptions are not transcribed. Once in the shrine it was probably rarely if e'er removed for utilise as a book.[13]

In the 16th century, when Durrow Abbey was dissolved, the book went into individual buying. Information technology was borrowed and studied past James Ussher, probably when he was Bishop of Meath from 1621 to 1623. Information technology managed to survive during that period despite at least ane section of information technology being immersed in water by a farmer to create holy h2o to cure his cows. In the period 1661 to 1682 it was given to the library at Trinity College, together with the Book of Kells, by Henry Jones while he was Bishop of Meath. The shrine and cover was lost during the occupation by troops in 1689.[14] [two]

Carpet pages

-

Folio 85v

-

Folio 125v

-

Folio 1v (with holes)

-

Folio

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b c Moss (2014), p. 229

- ^ a b c d e f O'Neill (2014), p. 14

- ^ De Paor (1977), 96

- ^ "IE TCD MS 57 - Book of Durrow". The Library of Trinity College Dublin . Retrieved fourteen September 2018.

- ^ Meehan (1996), pp. 30-38

- ^ Chocolate-brown, Michelle (2003). The Lindisfarne Gospels: Society, Spirituality & the Scribe. London, The British Library: University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Wilson, 34, quoting some other writer (unnamed).

- ^ Meehan (1996), p. 53 & illustration p. 35

- ^ Meehan (1996), pp. 43-44

- ^ Meehan (1996), pp. 26-28, 2

- ^ a b Mitchell (1996), p. 29

- ^ Mitchell (1996), pp. 28-29

- ^ Meehan (1996), p. xiii

- ^ Meehan (1996), pp. 13-16

References [edit]

- Calkins, Robert G. Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1983.

- De Paor, Liam. "The Christian Triumph: The Golden Age". In: Treasures of early on Irish fine art, 1500 B.C. to 1500 A.D: From the collections of the National Museum of Republic of ireland, Imperial Irish Academy, Trinity College Dublin. NY: Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, 1977. ISBN 978-0-8709-9164-6

- Meehan, Bernard. The Book of Durrow: A Medieval Masterpiece at Trinity College Dublin, 1996, Town Firm, Dublin, ISBN 1-57098-053-five

- Mitchell, Perette. "The Inscriptions on Pre-Norman Irish gaelic Reliquaries". Proceedings of the Imperial Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, volume 96C, no. one, 1996. JSTOR 25516156

- Moss, Rachel. Medieval c. 400—c. 1600: Fine art and Architecture of Ireland. London: Yale University Printing, 2014. ISBN 978-03-001-7919-iv

- Moss, Rachel. The Book of Durrow. Dublin: Trinity Higher Library; London: Thames and Hudson, 2018. ISBN 978-0-5002-9460-four

- Nordenfalk, Carl. Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Painting: Book illumination in the British Isles 600-800. Chatto & Windus, London (New York: George Braziller), 1977

- O'Neill, Timothy. The Irish Paw: Scribes and Their Manuscripts From the Earliest Times. Cork: Cork Academy Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1-7820-5092-6

- Wilson, David Chiliad.; Anglo-Saxon Art: From The Seventh Century To The Norman Conquest, Thames and Hudson (US edn. Overlook Printing), 1984

- Soderberg, John. "A Lost Cultural Exchange: Reconsidering the Bologna Shrine's Origin and Use". Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, book 13, 1993. JSTOR 20557263

- Walther, Ingo. Codices Illustres. Berlin: Taschen Verlag, 2014. ISBN 978-3-8365-5379-7

External links [edit]

- The Library of Trinity Higher Online Exhibition on the Volume of Durrow

- The Library of Trinity College catalogue entry

- The Library of Trinity College full digitised Volume of Durrow

- Book of Durrow catalogue entry at Academy of Due north Carolina

- Treasures of early Irish art, 1500 B.C. to 1500 A.D., an exhibition catalogue from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online equally PDF), which contains material on the Book of Durrow (cat. no. 27)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_Durrow